I’ve been neglecting this blog for too long, in favour of my other one, but, as a person much addicted to reading, I’ve been impressed by a writer who’s been eloquently cataloguing global problems and solutions in the Anthropocene. Gaia Vince (I presume her parents were Lovelock fans) has written 3 books, Adventures in the Anthropocene, Transcendence and Nomad century, the first two of which I now possess, the first of which I’ve read, the second of which I’m well into, and the third of which I intend to buy. So, time to return to my own self-education notes on solutions…

Vince appears to be my opposite – adventurous, extrovert, successful, in demand, and doubtless eloquent in person as well as in print. Bitch! Sorry, lost it there for a mo. The heroes and heroines of her first book, the product of travels though Asia, South America, Africa and the WEIRD world, and the solutions they’ve created and pursued, will, I think, provide me with pabulum for many blog pieces as I sit, impoverished (but not by global standards), uneducated (in a formal sense) and unlamented in rented digs in attractive and out-of- the-way, Adelaide, Australia, once touted as the ‘Athens of the South’ (at least by Adelaideans).

What I’ve found in my research on solutions – and Vince’s explorations have generally borne this out – is that solutions to global or local problems have created more problems which have led to more solutions in a perhaps virtuous circle that’s a testament to human ingenuity. And the fact that we’re now 8 billion, with a rising population but a gradually slowing rate of rising (in spite of Elon Musk), shows that we’re successful and trying to deal with our success…

So what are our Anthropocene problems? Global warming, of course. Destruction of other-species habitats on land and sea. Damming of rivers – advantaging some groups and even nations over others. Rapid industrial change (I’ve worked – mostly briefly! – in a half-dozen factories, all of which no longer exist). Population growth – in the 20th century from less than 2 billion to over 6 billion, and over 8 billion by May 2023. Toxic waste, plastic, throwaway societies, social media addiction and polarisation, the ever-looming threat of nuclear warfare… and that’s enough for now.

But on a more personal level, there’s the problem of how to navigate the WEIRD world, a world that bases itself on individualism, that’s to say individual freedom, when you don’t believe in free will (or rather, when you’re certain that free will is bullshit). And yet… a lot of smart, productive people don’t believe in free will (Sam Harris, Robert Sapolsky, Sabine Hossenfelder), and it doesn’t seem to affect their activities and explorations one bit – and to be honest it doesn’t affect my work, such as it is, either, though it does provide me with a handy excuse for my failings. My introversion has been ingrained from earliest childhood (see the Dunedin study on personality types and their stability throughout life), my lack of academic success has been largely due to my toxic family background, bullying at school, and lack of mentoring during the crucial learning period (from 5 to 65?), and my lifelong poverty (within the context of a highly affluent society) is not entirely due to laziness, but more to do with extreme anti-authoritarianism (hatred of ‘working for the man’) and a host of other issues for which I blame my parents, my social milieu, my genes and many other determining factors which I’m determined not to think about right now.

Anyway, with no free will we humans have managed transformational things vis-à-vis the biosphere, and there will be more to come. In her epilogue to Adventures in the Anthropocene, Vince hazards some predictions, using the narrative of someone looking back on the century from the year 2100, and considering the book is already about ten years old, I might use the next few posts to look at how they’re faring.

So – nuclear fusion. Here’s Vince’s take:

In 2050, the first full-scale nuclear fusion power plant opened in Germany (after successful experiments at ITER, in France, in the 2030s), and by 2065 there were thirty around the world, supplying one-third of global electricity. Now, fusion provides more than half of the world’s power, with solar making up around 40% and hydro, wind and waste (biomass) making up the rest.

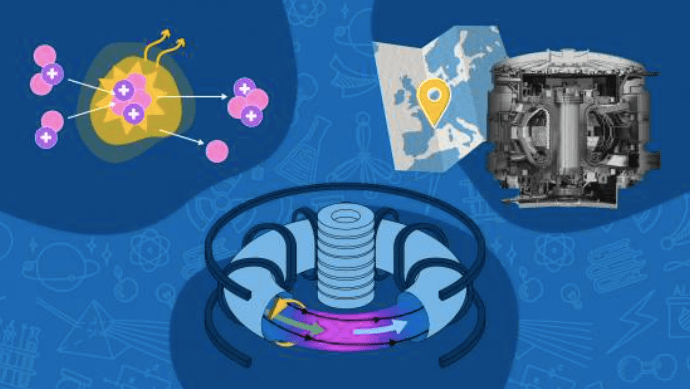

So I’m starting with a very recent video by the brilliant Matt Ferrell, as a refresher for myself. Nuclear fusion, the source of the sun and stars’ energy, involves two small atoms colliding to form a larger atom (e.g. hydrogen forming helium), with some mass being converted to energy in the process. And I mean a really large amount of energy. To quote Ferrell:

Once the fusion reaction is established in a reactor like a tokamak, a fuel is required to sustain it. There’s a few different fuels that are options: deuterium, tritium or helium-3. The first two are heavy isotopes of hydrogen… most fusion research is eyeing deuterium plus tritium because of the larger potential energy output.

The power released from fusion is much greater, potentially, than that derived from fission. And deuterium plus tritium produces neutrons, which creates a process called neutron activation, which induces relatively short-lived but problematic radioactivity. And there are a host of other challenges, but it’s clear that incremental progress is happening. People may have heard of JET (the Joint European Torus) and the unfinished ITER (the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor), and of recent promising developments – for example, this:

A breakthrough in December 2022 resulted in an NIF [Nuclear Ignition Facility] experiment demonstrating the fundamental scientific basis for inertial confinement fusion energy for the first time. The experiment created fusion ignition when using 192 laser beams to deliver more than 2 MJ of ultraviolet energy to a deuterium-tritium fuel pellet.

Ferrell visited the Culham Science Centre, near Oxford in the UK, where he was shown through the RACE (Remote Applications in Challenging Environments) facility, a perfect acronym for the time. They’ve created a system there called MASCOT, which appears to be a cyborg sort of thing, but mostly mechanical – with a human operator. The aim is to incrementally develop complete automation for maintenance and upgrading of these highly sensitive and potentially dangerous components. Since everything is still at the experimental stage, with a lot of chopping and changing, flexible human minds are still required. Full automation is clearly the goal, once a reactor is up and running, which is still far from the case. Currently, it requires about a thousand hours of training to work with the machinery and the haptics in this pre-full automation stage, bearing in mind that the types of robotic and cable systems are still being worked out. Radiation tolerance is an important factor in terms of future developments. Culham uses a ‘life-size’ replica of a tokamak for training purposes.

RACE, as the acronym suggests, is not just a facility for nuclear research but for dealing with hazardous environments and materials in general. Moving on from JET, Ferrell visited the new MAST-U (Mega Amp Spherical Tokamak – Upgraded!). As Ferrell points out, the long lag time between promise and results in nuclear fusion has often been the butt of jokes, but this ignores many big recent developments, described well by Dr Melanie Windridge in a Royal Institute lecture, of which more later.

In the video we see a real tokamak from the sixties, probably the first ever, sitting on a table, to indicate the progress made. MAST-U’s major focus at present is plasma exhaust and its management, essential for commercial fusion power. Its new plasma exhaust system is called Super-X, a load-reducing divertor technology vis-a-vis power and heat, so increasing component lifespans. One of the scientists described the divertor as like the handle in a hot cup of coffee:

So our plasma is the coffee that we want to drink. It’s what we want, right? We want this coffee as hot as possible, but we won’t be able to handle it with our hands, we need a handle, and the diverter has the same function, it tries to separate this hot, energetic plasma from the surface of the device. So we divert the plasma into a different region, a component specifically designed to accommodate this large excess energy.

The divertor is the key factor in the upgrade and is drawing worldwide attention, as it has supposedly improved plasma heat diversion by a factor of ten, as I understand it. And MAST-U’s spherical design is potentially more efficient and cheaper than anything that has gone before. All a step or two towards more viable power plants. And, returning to JET, you can see in the video how massive the system is compared to the table-top version of the sixties. JET came into being in the 80s, and has had to deal with and adapt to many new developments, such as the H-mode or high-confinement mode, a new way of confining and stabilising plasma at higher temperatures, which has gradually become standard, requiring engineering solutions to the torus design. It’s expected that AI will play an increasing role in new incremental modifications. Simulations to test modifications can be done much more quickly, in quicker iterations, via these advances. AI, computer modelling and advances in materials science and superconductors are all quickening the process. JET will be decommissioned in about 12 months, but much is expected to be gleaned from this too, as they look at how neutrons have affected material components.

Another issue for the future is tritium, supplies of which are currently insufficient for commercial fusion production. According to ITER, current supply is estimated at 20 kilos, but tritium can be produced, or ‘bred’ within the tokamak through the interaction of escaping neutrons with lithium. Creating a successful tritium breeding system is essential due to the lack of external sources.

Okay, I’ve gone on too long here – I’ll post more of this topic soon.

References

Gaia Vince, Adventures in the Anthropocene, 2014.

How We’re Going To Achieve Nuclear Fusion (video – Matt Ferrell,Undecided)

Could nuclear fusion energy power the future? with Melanie Windridge – Royal Institution video